Are you struggling to get a handle on your first scholarly book? To see clearly not just what you have, but where it’s ultimately going? Do you feel stuck in revisions—like you’re adding and changing text in your chapters, but there’s no end in sight? Or are you reluctant to sit down and write because you don’t know what you’re arguing, and you’re afraid you’ll be wasting your time?

What you need is a way to assess the book as a whole before you’ve finished writing it. You need to work ON your book, not just IN it. If you do this, you’ll be able to make a plan—a plan that will show you where to invest your precious time and energy.

What you need, in other words, is The Dissertation-to-Book Workbook. My co-author and I wrote it for writers just like you. But if you don’t have it on hand right now, read on.

The Difference between Working IN Your Book and Working ON Your Book

Working ON your book means working at the level of your book as one object. When you work ON your book, you clarify its structure, narrative arc, and how you prove your argument from the outside in.

When you work ON your book, you are not revising or generating prose in any one piece of the book.

Working IN the book is what you are likely doing right now. It means generating new text in your chapters and revising what’s there.

When to Work ON Your Book instead of IN It

In my experience, working ON your book is useful at a very specific time: after you have been revising for a minimum of 4 months. You should be fairly sure of where your book is headed and have at least 80% of the material drafted. The main goal of working ON your book is to get a handle on what’s there and imagine the book it will become as its own unit.

You should definitely work ON your book before your prepare or submit your book proposal.

Before working ON your book, you will think you know what your book does.

But working ON your book will force you to clarify many decisions you’ve made without realizing it. Consequently, not only might your book’s structure and scope change significantly after doing this work, but your understanding of what your chapters do in service of your larger book might also shift as well.

[Note: The broad activity below is an extremely general overview of the two most critical pieces of our Dissertation-to-Book Workbook.How to Work ON Your Book

For first-time book authors, the trickiest part about humanities books is that they are more than the sum of their chapters. Your main argument will have several interconnected threads running through your book and keeping a handle on them all is practically impossible if you only ever work IN your books’ individual chapters.

You likely know what your book’s main argument and interventions are but might never have fully articulated the other main narrative threads connecting its chapters.

I’ve found that the best way to make these connections is to start with questions.

Articulating and Evaluating Book Questions

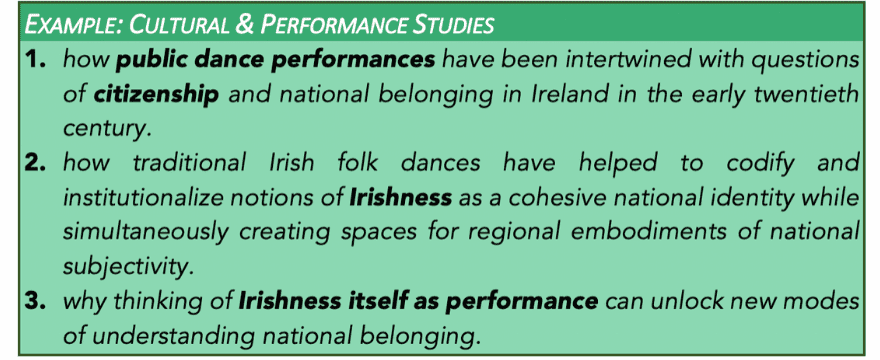

Write out 3 main book questions. Ask yourself: “What are the most important questions that my book asks and answers about its body of evidence?” The “body of evidence” part is crucial—these can’t be big-picture questions like “Why is X important?” Instead, think more concretely: “How does X happen across various domains?”

Here’s a quick primer on book questions:

Your book questions should be questions that the book as a whole asks, not questions that are specific to the chapters. In other words, each chapter should give an answer to every question.

Note: authors must typically revise their book questions at least four times, paying attention to vocabulary, relationships between key ideas, actors and actions, sentence structure, and directionality.

(Want more examples, drafting exercises, revising exercises, and checklists to ensure you’re on the right track? You’ll find tons of them in The Dissertation-to-Book Workbook.)

Writing Chapter Answers

Next, choose one chapter. For each book question, write one chapter-level answer. Keep it to one sentence. In other words, articulate how this chapter adds something to move this narrative thread forward.

Note: The chapter answers exercise is the most challenging piece of working ON your book because it will force you to align your chapters’ claims with your book’s. Often problems like outlier chapters, inconsistent terminology, or fuzzy logic will reveal themselves through the chapter answers. For more help, see Chapters 9–10 of The Dissertation-to-Book Workbook.

(Want more ideas of what you should be asking yourself at this stage and how to evaluate your project? Check out our Dissertation-to-Book FAQ Playlist.)

What You Will Realize When You Work ON Your Book

Here are a few things you will likely learn in this process:

- Because you had never forced yourself to explicitly articulate logical connections between the book and its chapters (or between different chapters), you will likely discover many implicit logical connections that don’t necessarily hold up under further scrutiny.

- Your terminology might not remain 100% consistent over the course of the book. You might now need to clarify your terms.

- Your book’s structure and content are interdependent. Changing chapter order or scope will bring different elements of your argument to the fore. You might have understood this intellectually before, but now deliberately evaluating and revising your book’s structure will make this concrete for you.

Wondering what we mean by “your book’s structure and content are interdependent?”

What Makes Working ON Your Book Feel Harder than Working IN It

As I described above, working ON your book involves deliberately clarifying the book- and chapter-level structure and organization with an eye to the main threads you will be weaving throughout your book.

In my experience, and as I describe more in-depth below, at about the 4-6 month period, you must work ON before you continue to work IN your book. But many first-time book authors struggle to do so.

Why?

There are two main reasons.

First, the work you do when you work ON your book is invisible and intangible. Unlike working IN your book, you are producing a structure, not necessarily words you will use in your final chapters (though, as I outline above, you will likely use some of this writing in your book’s and chapters’ introductions).

Second, clarifying the logic that holds your book together and then significantly revising your book can make you feel like you’re going backwards because it’s revealing the distance between what you have now and what you want to have by the end.

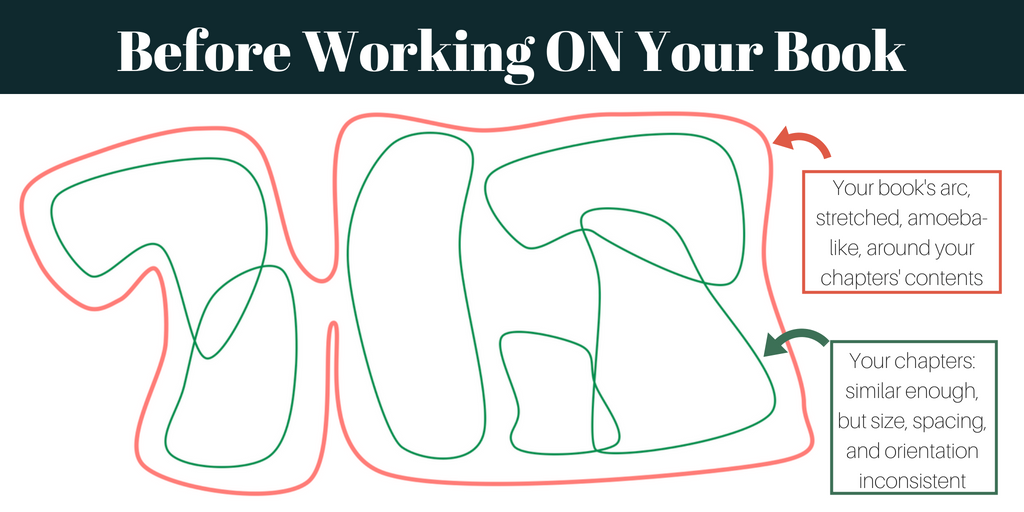

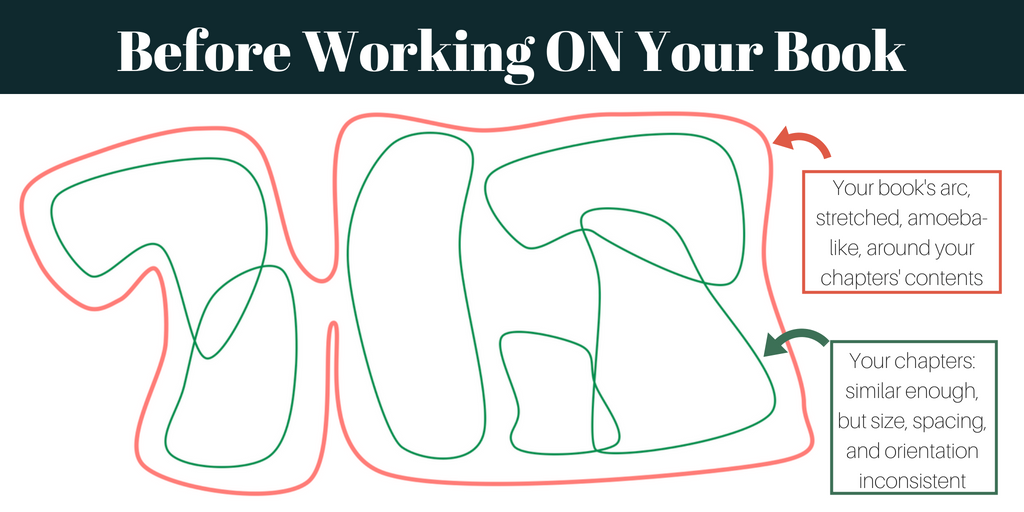

Here’s what you can imagine your book looks like before you work ON it.

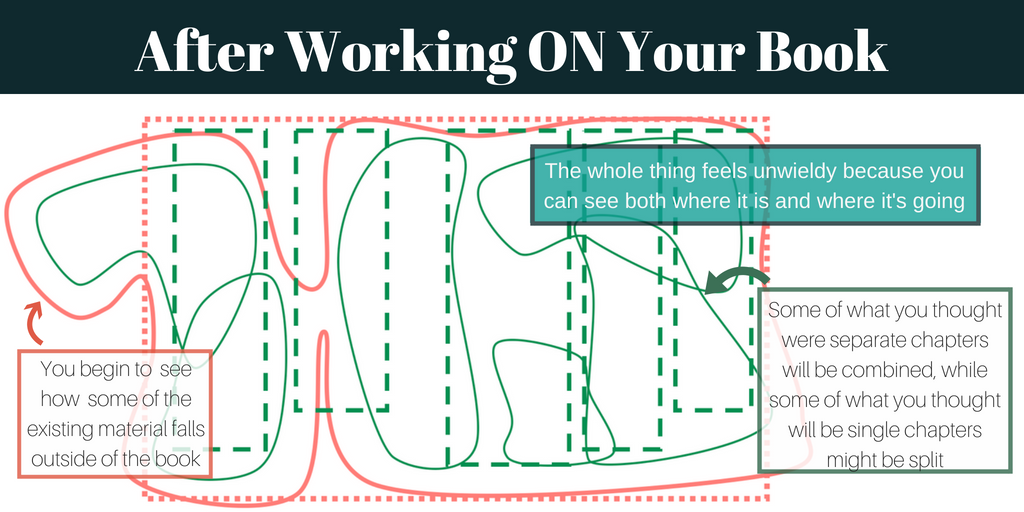

And here’s what you produce when you work ON your book: a clear plan.

But then there’s the final step: remapping where you’re going onto what you have.

Just looking at this picture can make you overwhelmed.

Yet without this work, your book might continue to resemble an amoeba. The rest of your revising time (stage 2 in my 7 stages model) will be spent getting your chapters to match your plan, section by section.

Why You Need to Work ON Your Book before Continuing to Work IN It

Once you reach the 4-6 month revision point, you know where your book is going and what it has to contribute, working ON your book is critical, for a few main reasons.

First, consider this image of your book before you work ON it again. Do you think continuing to add material will straighten it out?

No.

Continuing to add material to the chapters is not going to make your book less of an amoeba. In fact, doing so might make it worse! Until you have your clear path laid out, continuing to revise means you risk making tangible progress on something that does not ultimately belong in your book.

Conversely, working ON your book before you continue to revise IN your book means that you will ensure all the time you spend revising is ultimately useful.

Additionally, this process of making and justifying the 2,383 decisions that make up your book–if only to yourself–will make you more confident about your book as a whole. This confidence will come across in your prose, proposal, and conversations with editors.

Here’s what we typically tell authors:

Finally, solidifying and narrativizing your book’s structure will help you write a clearer book introduction and strong chapter introductions. You can also use this writing in your proposal and conversations with editors.

How Long Working ON Your Book Will Take

The process took me about 60 hours, spread over eight weeks. But, this time included figuring out the process as I went, and the process I developed was not nearly as in-depth as The Dissertation-to-Book Workbook.

It now regularly takes readers about 46 hours on average, working at their own pace, to distill their book’s main priorities, ensure their structure best serves their overall book-level claims, lay out what each of the chapters tangibly contributes to the project, and refine its narrative arc.

Ready to Work ON Your Book?

Knowing you need to work ON your book is one thing; doing it is another. That’s why I wrote The Dissertation-to-Book Workbook: to give you practical, actionable exercises that walk you through this process. You don’t need to come up with your own process—just open the workbook to page 1 and begin. And as you work through it, you’ll find helpful tips, examples, common stumbling blocks, and “aha!” moments from authors who’ve been there. You aren’t alone!